SPIN ESR 3.1: Optimal Design of Experiments and Surveys for Scientific Interrogation

Host institution: University of Edinburgh, U.K.

Supervisors:

| main supervisors: | Andrew Curtis, Ian Main (GeoSciences, Edinburgh, UK) |

| external supervisor: | Hansruedi Maurer (ETH Zurich, CH) |

This position is filled

Project description

No methods exist to design surveys and experiments for scientific interrogation, such that recorded data optimally constrain the answers to questions of interest. You will create the first.

Scientists try to answer questions about the state and dynamics of nature, often using experiments to discriminate between competing hypotheses, or to constrain the parameters in particular theories. Answering specific questions using experimental data of any type is called an Interrogation.

Many millions of pounds are spent each year on conducting such scientific experiments, yet in Geophysics these experiments are usually not optimally designed. A well-designed experiment is one that is expected to provide most possible information about questions of interest given a budget of time/money/equipment. Designing an optimal experiment is challenging: first we must be able to estimate the information that we expect any particular experimental design to provide; then we must search for the design that will provide the most useful information. This is an optimisation problem. It can be solved for experiments with simple, linear relationships between data and parameters of interest, but standard geoscientific problems are significantly nonlinear which creates a far harder, computationally challenging design problem.

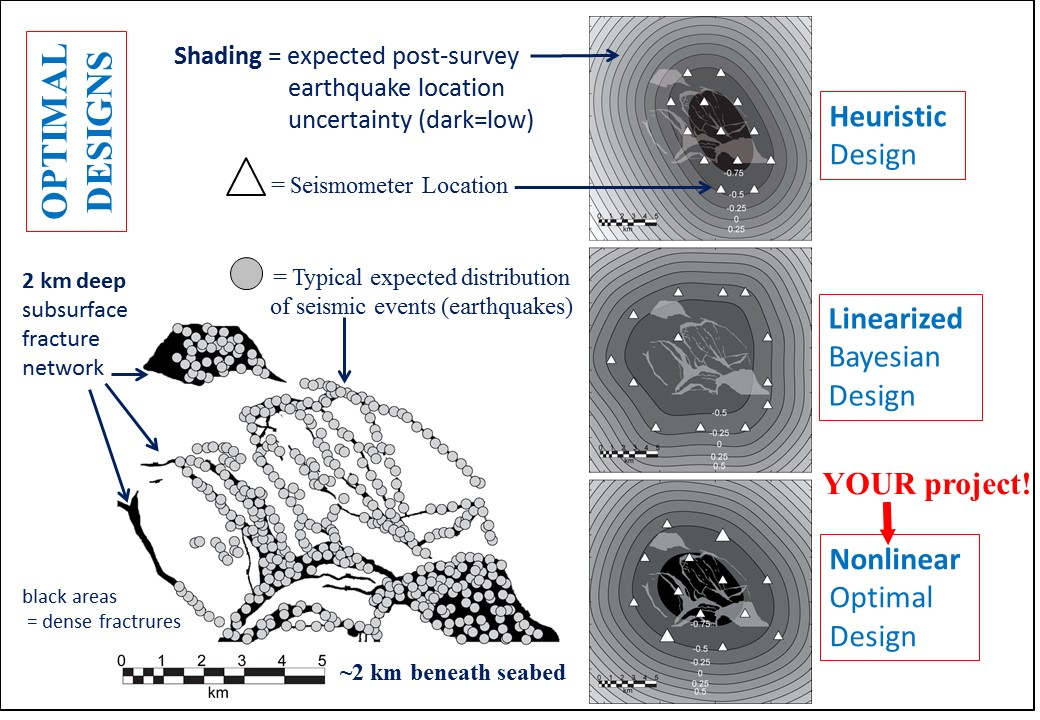

Three designs (right column) of seabed seismic sensor arrays (triangles) to monitor an expected distribution of earthquakes in a fracture network (left). Designs were found using different design methods: heuristics (rules of thumb), linearised (approximate) physics, and fully nonlinear optimal design (your project). Darker shading indicates best location results.

Three designs (right column) of seabed seismic sensor arrays (triangles) to monitor an expected distribution of earthquakes in a fracture network (left). Designs were found using different design methods: heuristics (rules of thumb), linearised (approximate) physics, and fully nonlinear optimal design (your project). Darker shading indicates best location results.

In the example depicted above, arrays of seismometers are deployed on the seabed to help us to locate earthquakes that occur in the Earth’s subsurface. The survey design should depend on where earthquakes are likely to occur, and on how waves propagate to each seismometer, both of which are uncertain. Assuming that locations of future earthquakes are likely to lie somewhere within the fracture network mapped in the image above, it is possible to design experiments to constrain their locations using heuristic (rule of thumb) design methods, linearised design methods, and fully nonlinear methods (three designs on the right in the image above). However, currently all such methods are approximate, in order to reduce computational cost. They also do not optimise the experiments to interrogate meta-questions like, “Over what fraction of the Earth’s subsurface is stress released by earthquakes?”

You will further develop sophisticated, fully-nonlinear, Monte-Carlo and machine-learning methods to evaluate the quality of experimental designs more efficiently than is currently possible. You will evaluate the extent to which using costly, nonlinear methods improves designs. You will apply your novel methods to key areas of geoscience: seismic imaging, electromagnetics, or human elicitation (questioning experts, e.g., to evaluate geological risks and hazards), and disseminate your methods and codes for the scientific world to use.

Key Research Questions

- For what types of interrogation problem can experiments or surveys be designed optimally?

- In which areas of science can we usefully solve such problems?

- What value is added by using optimal designs over heuristic designs?

Methods and Plan of Activities.

- Year 1: Learn about existing design methods; identify which ones may solve geoscientific interrogation problems that are of interest to you, and choose one on which to focus. Develop novel design methods as necessary, and conduct computational tests to evaluate their success. This will lead to your first scientific paper from this project.

- Year 2: Collaborating with other SPIN PhD candidates, design an experiment for a real scientific question. Acquire experimental data that allows different designs to be compared. Analyse these to identify the best-performing design method – leading to a second paper.

- Year 3: Deploy the methods to design different experimental types; help people to optimise their surveys and experiments in different domains across the (geo)sciences. Apply the new methods to design human elicitation experiments. Write papers as opportunities arise.

Training

You will receive training in all necessary design and optimisation methods, and multidisciplinary training for your chosen experimental types (e.g., remote sensing data of various kinds such as seismic/radar data measured from the ground surface, air or satellite, and expert elicitation methods). You will learn how to program high-performance computers efficiently, and will be rooted in your supervisors’ leading research groups on geophysical and mathematical methods. You will receive support to attend national and international conferences and workshops to disseminate findings to the scientific community, and learn to prepare and submit scientific papers to internationally peer-reviewed literature. You will benefit from collaborating within an international team of 15 ESR’s across Europe within SPIN, extending your experience far beyond that of a stand-alone PhD.

Further Reading: For general information about optimal design methods see the tutorials:

Curtis, A. (2004a,b) – pdf’s available at: https://blogs.ed.ac.uk/curtis/publications/