Research

Seismology is the science of studying measured mechanical vibrations of the Earth. These vibrations are caused by seismic waves propagating through the planet’s interior. Just as we use ultrasound for medical imaging, seismic waves provide a window through which to view our planet’s interior. They can be used to warn of upcoming volcanic eruptions and tsunami by detecting earthquakes, to determine subsurface structure, and to investigate the nature of our planet. And just as new developments in ultrasound technology allow us to monitor processes in the human body1 (motion, flow, change of stiffness), seismological methods are now commonly used to continuously monitor earth processes and their associated hazards such as earthquakes, permafrost melting, river flow, landslides, glacier motion and avalanches.

Currently, for the first time in decades, revolutionary changes in how we measure seismic waves are emerging, using novel technologies such as fibre-optic (communication) cables, rotational motion sensors, and extremely dense networks. These new sensing technologies record the wavefield with high spatial resolution, and they are reaching a level of maturity where we can incorporate them into seismological applications.

Furthermore, over the last decade, the emergence of methods that use ambient seismic waves or ‘noise’ led to numerous observations of dynamic variations in seismic wave speed2 3 4 5 6; these cannot be explained by classical seismology which would predict constant seismic velocities. To-date, our interpretations of velocity variations associated with earthquakes, the onset of volcanic eruptions and landslides7 8 9 remain phenomenological. This is related to the fact that seismology is largely based on a simplistic model of material behaviour adopted a century ago: namely, the linear relation between applied stress and resulting deformation known as Hooke’s law. However, on scales relevant to natural hazards, the mechanical behaviour of rocks, sediments and other microinhomogeneous materials such as concrete can be very complex. This can lead to far more complex wave propagation phenomena10 than that usually accounted for in global or regional wave propagation theory.

This is where the unprecedented dense spatial sampling of the wavefield, or direct access to local deformations or wavefield gradients11 provided by the new sensing technology will play an important role. It allows us to relax our assumptions on wavefield properties, and instead exploit the information contained in the wavefield in its full complexity. The wavefield gradients in particular are more sensitive to local, small-scale heterogeneities and changes in the subsurface12.

However, these new observations that are inexplicable by current seismological theory have two implications: (1) We must adapt our physical theoretical framework to prepare for the next generation of imaging and interrogation techniques that use the unprecedented detail of new wave observations provided by these novel sensing technologies; (2) Seismology can provide much more information about the subsurface than currently exploited. This disruptive convergence of ground motion sensing technology and observational evidence for dynamic variations in the mechanical behaviour of Earth’s materials, reveals the potential for revolutionary progress in our ability to image, monitor and understand dynamic earth processes associated with natural hazards.

Since the new sensor types are not yet widespread, there are still few young scientists worldwide with the knowledge necessary to apply them. We will train the next generation of experts who have the skills and background to incorporate emerging observation technology to address challenging science problems related to monitoring natural hazards. They will have a deep understanding of the new sensor technology, including the strengths and limitations of each type. They will learn how to design experiments so that different sensors are used optimally, depending on the process that should be studied and the physical phenomena that likely play a role. This will all be based on a solid comprehension of wave propagation physics in complex media.

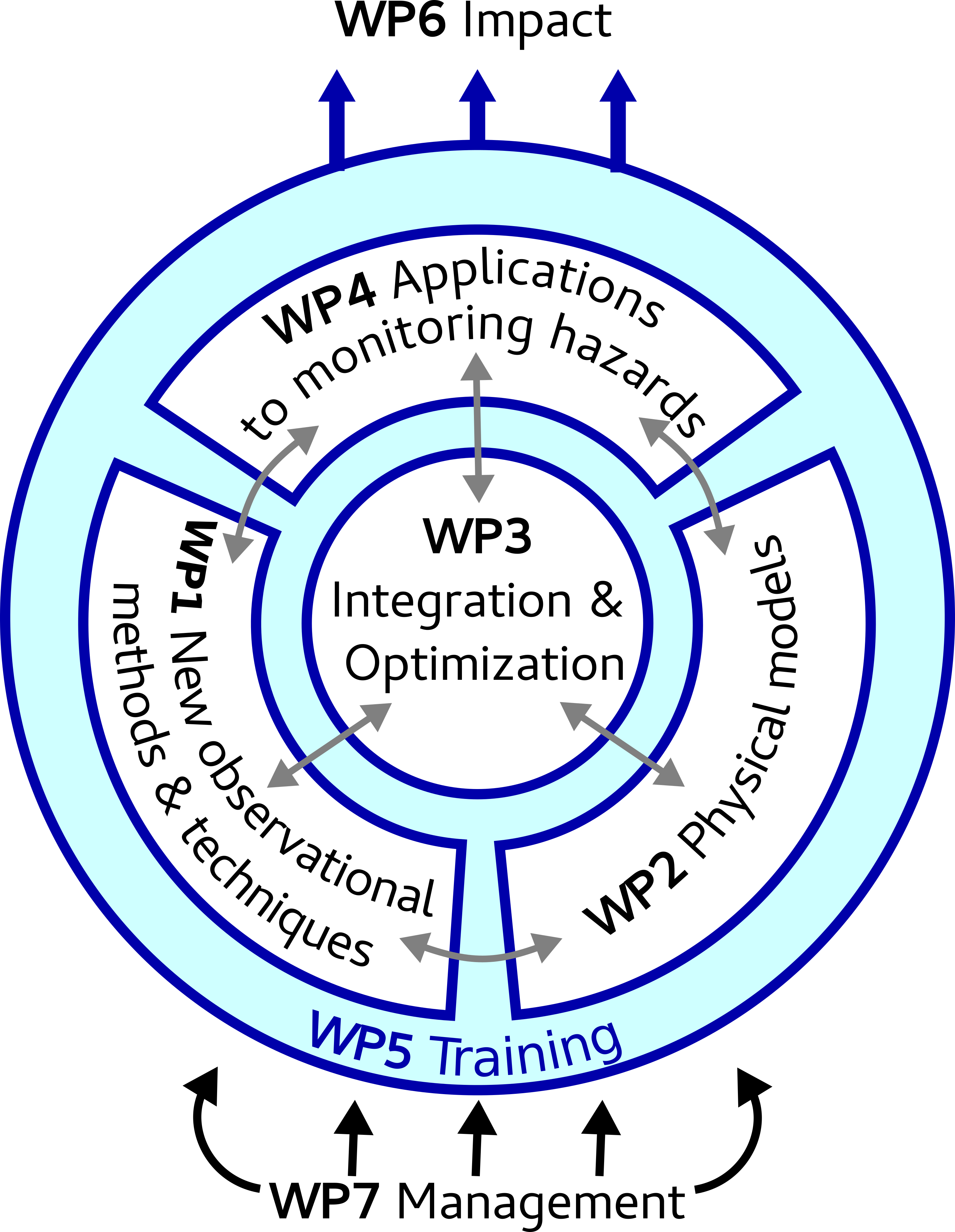

Our research strategy covers the entire workflow from instrument via physics to monitoring applications: WP2 develops and tests new physical models of transient subsurface changes, allowing conception of entirely new observation and sensing strategies to be developed in WP1. At the interface between the scientific work packages is WP3, providing the methodological framework for optimal experiments for specific research questions and applications. All these WPs provide input to the hazard and monitoring applications to be addressed in WP4. The scientific WPs complement each other, and are all embedded into the training WP. Research output of SPIN flows into impact and dissemination activities, and SPIN is supported overall by the management WP.

Individual projects

The following 15 PhD projects are distributed among the 4 research work packages:

| Project | Host Institution | Project title |

|---|---|---|

| WP1 | ||

| SPIN ESR 1.1 | LMU Munich (D) | Harnessing wavefield gradients: theory, experiment, applications |

| SPIN ESR 1.2 | ETH Zürich (CH) | Distributed acoustic sensing for natural hazard assessment |

| SPIN ESR 1.3 | Université Grenoble Alpes (F) | Wavefield gradient methods to monitor the Earth’s crust |

| SPIN ESR 1.4 | IPGP Paris (F) | Ocean floor seismological and environmental monitoring |

| WP2 | ||

| SPIN ESR 2.1 | GFZ Potsdam (D) | Rock mechanics and Seismology |

| SPIN ESR 2.2 | University of Edinburgh (UK) | Understanding Earthquake-Induced Damage & Healing of Crustal Rocks |

| SPIN ESR 2.3 | British Geological Service (UK) | Next-Generation Physics-based earthquake forecasts |

| WP3 | ||

| SPIN ESR 3.1 | University of Edinburgh (UK) | Optimal Design of Experiments and Surveys for Scientific Interrogation |

| SPIN ESR 3.2 | LMU Munich (D) | Numerical models across the scales |

| SPIN ESR 3.3 | Université Grenoble Alpes (F) | Detection and characterization of seismic signals with dense arrays of new seismological instruments |

| SPIN ESR 3.4 | University of Hamburg (D) | Ambient signals as a tool to characterize material properties |

| WP4 | ||

| SPIN ESR 4.1 | DIAS Dublin (IE) | Ground motion and unrest triggering on volcanoes |

| SPIN ESR 4.2 | University of Hamburg (D) | Nonlinear seismology meets structural health monitoring |

| SPIN ESR 4.3 | ETH Zürich (CH) | Monitoring hazards from a changing alpine environment |

| SPIN ESR 4.4 | GFZ Potsdam (D) | Distributed Acoustic Sensing and Volcano-seismology |

References

-

Rix, Anne, et al. (2018) Advanced Ultrasound Technologies for Diagnosis and Therapy. The Journal of Nuclear Medicine 59.5, 740-746. ↩

-

Sens-Schönfelder & Wegler, U. (2006) Passive image interferometry and seasonal variations of seismic velocities at Merapi Volcano. GRL 33.21. ↩

-

Brenguier, F. et al. (2008) Postseismic relaxation along the San Andreas fault at Parkfield from continuous seismological observations. Science 321(5895) ↩

-

Chen, J.H. et al. (2010) Distribution of seismic wave speed changes associated with the 12 May 2008 Mw 7.9 Wenchuan earthquake. GRL 37.18 ↩

-

Meier, U. et al. (2010) Detecting seasonal variations in seismic velocities within Los Angeles basin from correlations of ambient seismic noise. GJI 181(2). ↩

-

Rivet, D. et al. (2016) Seismic velocity changes associated with aseismic deformations of a fault stimulated by fluid injection. GRL 43(18) ↩

-

Obermann, A. et al. (2013) Imaging preeruptive and coeruptive structural and mechanical changes of a volcano with ambient seismic noise. JGR: Solid Earth 118(12), 6285-6294. ↩

-

Gassenmeier, M. et al. (2016) Field observations of seismic velocity changes caused by shaking-induced damage and healing due to mesoscopic nonlinearity. Geophys. J. Int. 204(3), 1490–1502. ↩

-

Mainsant, G. et al. (2012) Ambient seismic noise monitoring of a clay landslide: Toward failure prediction. JGR: Earth Surface, 117(F1). ↩

-

Ostrovsky, L.A. & Johnson, P.A. (2001) Dynamic nonlinear elasticity in geomaterials. La Rivista Del Nuovo Cimentó 24(7), 1–46. Part B1 - Page 5 of 34SPIN - ETN ↩

-

Donner, S. et al. (2017) Comparing direct observation of strain, rotation, and displacement with array estimates at Piñon Flat Observatory, California. Seism. Res. Lett., 88(4), 1107-1116. ↩

-

Singh et al. (2020) Correcting wavefield gradients for the effects of local small-scale heterogeneities. Geophys. J. Int. 220(2), 996–1011. ↩